Yesterday, our workshop took place at the UFFestival. Born from an idea that had been in the air for a long time, we managed to bring together higher education experts from six non-European countries. In the nearly two hours, they presented their perspectives and experiences and exchanged ideas with the participants.

The unifying element of the presentations was how quality and access to higher education can be improved. The approaches range from conceptual further development of instructional design principles, through the reflection of the concept of “quality” against the backdrop of racism and inequality, to the development of hybrid teaching to maintain access to higher education in times of natural disasters.

Exchanging ideas with committed people from the higher education sector across continents is often an eye-opener for me in the truest sense of the word. I always have the arguments from Jürgen Straub’s booklet “Understanding, Criticism, Recognition”1 running through my mind, in which he explains that understanding the unfamiliar cannot occur without critically questioning one’s own perspective.

“Those who adopt something foreign without looking closely at what it [understanding the foreign J.H.] involves will end up holding only their own ideas – thus gaining nothing new, not even new insights and knowledge.”

(Straub, 1999, p. 14, own translation)

I do not know if I can already call this “insights and knowledge,” but a few things have stuck with me:

- There are differences between countries and over time within countries in how strongly top-down or bottom-up approaches are represented in higher education development. My impression, for example, is that we in Germany foster a rather strong bottom-up culture. However, decisive changes (for better or worse) apparently come with top-down initiatives.

- The role and status of professors are defined differently and are in flux. The central question is to what extent experts from practice are integrated into academic teaching. A growing “mismatch” between higher education training and the competencies required by the job market was an international phenomenon. A scientific culture that maintains boundaries is a disadvantage, with interdisciplinarity not being highly valued.

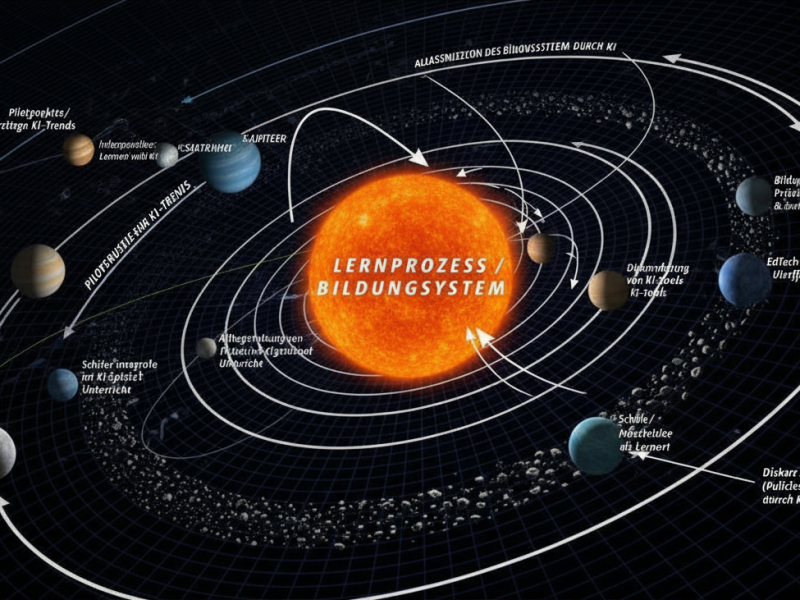

- There are problems that (at first glance!) sound similar: competency development, higher education in an AI world, changes in teaching styles, access, and exclusion come to mind. However, there are also solutions and approaches to solutions, but these are unevenly distributed. Moreover, things that are considered solutions by some are regarded as problems by others.

The workshop was entitled “(un)common grounds”. University cultures may not differ so much in the challenges at the level of dialog. However, they differ more in how urgently and significantly such problems are addressed in the various regions.

- Straub, J., 1999. Verstehen, Kritik, Anerkennung: Das Eigene und das Fremde in der Erkenntnisbildung interpretativer Wissenschaften. Wallstein [↩]