Today, a classic educated middle-class introduction:

When philosophy paints its gray on gray, then has a form of life grown old, and with gray on gray it cannot be rejuvenated, but only known; the Owl of Minerva first takes flight with twilight closing in.

G. W. F. Hegel in the Preface to the “Philosophy of Right”, 1820

Of course, there are countless interpretations and criticisms of this beautiful classic picture. What Hegel probably meant by this he has largely explained himself in other places: The old, owly philosophy can only interpret the conditions adequately when they already begin to become obsolete when “the form of life has become old”. This is more than an “afterwards you are always smarter”. It is also about the fact that we must take a step back to see the big picture, that it takes time to perceive the details, that the analysis follows what is happening. In other words, everything that we are not experiencing with AI/AI/ChatGPT right now.

What’s actually happening?

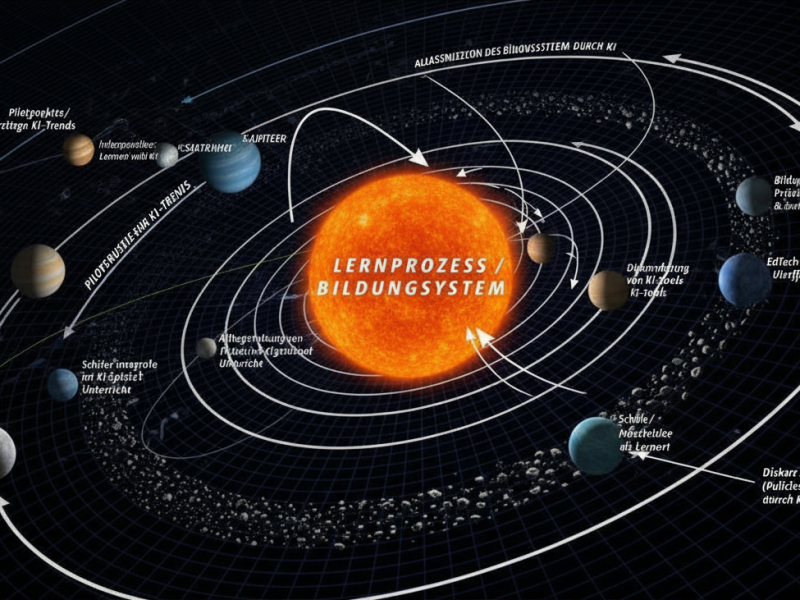

What has happened in the last few weeks in regard of ChatGPT, AI/AI, Large Language Models etc. takes my breath away. It is not so much the astonishing capabilities of the new generation of AI that make me dizzy, but the rapid speed at which the discussion in the university community has developed. It seems like the entire learning curve that technology acquisition can have been being completed in a hurry. You could say that since last December, the university community has gone through all the stages of media literacy development, which are a) understanding, b) application, c) criticism. And the framework conditions have also been defined. Legal issues, resources, teaching methods, organizational development, values – the decisive questions are asked, and the requirements are formulated for all aspects. Likewise, the use of the chatbot to promote critical thinking has already been (conceptually) bagged and the necessary new forms of university organization are also available in thesis form. I feel challenged by this, to say the least, and ask myself, what is actually happening? So far, I’m a bit at a loss. There is a growing impression that something incredibly important is happening here and now. But when I try to grasp what is happening, I feel as if I want to read the name of the station through which the train is racing.

Collective Pressure to act.

We seem to be under a gigantic pressure to act. Understanding and designing can no longer take place one after the other but must happen simultaneously to keep pace. This may not be a bad thing in itself, because designing can be a good way to understand better. And in contrast to the great philosopher Hegel, we probably see neither the necessity nor the possibility of packing the whole of reality into a complete, ultimately true system. “Rough consensus and running code” is more the mode in which we move towards stable systems today. Unfortunately, however, this also leads to the fact that every new turn in technological development, social discussion (AI moratorium, German ethics council) and regulation (Italy) demands that we be readjusted. Reality tends to evolve simply, it is man-made, but nevertheless not easily accessible to human thought.

(Academic) Culture is “not given abstractly, but produced in the multiple situations in which we live and act. Culture becomes tangible in these moments, but we do not immediately grasp it. We need distancing or alienation in order to develop an awareness of it.”

Langemeyer, Schraube & Tremp, 2022, p. 10 (own translation)

This is abhorrent to pedagogical thinking, because the careful design and fine-tuning of the learning environment is his maxim of action. We act in terms in the absence of a developed reality, we try to anticipate and plan the application of technology, even without knowing it exactly. For this to succeed, we need at least a few basic “rules of thinking”. The interesting thing is that, on the one hand, we live in times of provisionally and unpredictability, but that the patterns of cognition and action are extremely stable and unmoved.

Rigid Patterns in turbulent Times

An exemplary piece for me is the LinkedIn thread, which had developed on the basis of a contribution by Andreas Wittke (in German). It contains all the elements of this pattern that makes me pay attention, and which seems to be universal. With the “Fenn diagram” aka “hype cycle” in mind, this course can be further differentiated.

- The need for change builds up in sight, as a threat, potential or object of learning – depending on the point of view. But the experts, visionaries and admonishers are already working on it. Tackle the new is already underway.

- The tipping point is reached at which the change develops exponentially. At this point, it can hardly be ignored and comes into use en masse, the iPhone moment of AI. It seems ubiquitous. Disruption, emerging traits. The change is felt uncontrolled and anarchic.

- There are many different speeds, whoever says “disruption” (“everything will be different”) or “dystopia” (“downfall of humanity“) (or something similar) first wins.

- Everyone says in chorus that something really must change now. The choir is reinforcing itself, so the change can no longer be argued away. But now something really must change!

- Even the tedious steps are set in motion. However, organizations and institutions cannot be changed as quickly as it seems urgent. There are many questions to be answered: What should be changed again, how exactly? What costs, how many jobs we need? Who decides?

- There is an adaptation to the new situation. According to the rules of assimilation, however, adaptation will only take place until equilibrium is restored. It is therefore unlikely that something will change fundamentally. It’s more of a groping readjustment of behavior and attitudes until the situation seems manageable again.

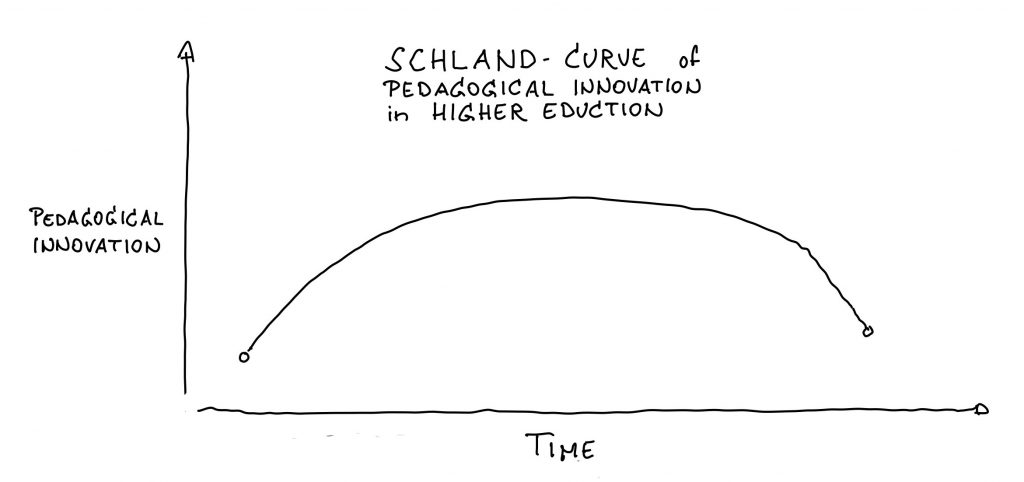

After all, the disruptively new is clocked in. Somehow the new situation has been managed, many things are worse, bumpier, and more critical, maybe some things are better. Overall, however, it continues as usual. If you know this pattern, then the last stages are already in sight at the tipping point, which usually end with comparatively minimal progress. This doesn’t feel like upheaval, but rather like the “Schland((Clipping of “DeutSCHLAND”. Gained media attention during the 2006 and 2010 World Cups))-curve of pedagogical innovation in higher education”.

However, the pattern of progression is not a law of nature. What is missing is, for example, to include ourselves as actors in the calculation and to determine to what extent we ourselves are biased in our patterns of thought and action and how they work. This is the message of the Minerva parable: We are to take in the whole event, including our own actions and position in it. And this is usually easier when perception does not get stuck on details (“gray in gray”). In my opinion, what would inevitably have to follow from such a consideration would be a “learning” that goes beyond a political, curricular, and didactic-methodological management of the new situation. Isabelle Buck and Anika Limburg recently summed it up nicely:

“As often as the idea of lifelong learning has been mentioned and used as a decorative accessory in the sense of a melodious phrase, its consistent implementation is now urgent in view of the rapid technological development. This means that the group of learners no longer includes only students, but consistently all members of the university.”

Buck and Limburg, 2023, p. 81 (own translation)